Reversing a DRM

Nov 21, 21This article was written with @MrMoDDoM and is available on his website as well.

A couple of weeks ago we stumbled upon a media renting service employing a custom DRM system. Being curious (and somehow allergic to DRM as a whole), we decided to dig into it and see how deep was the rabbit’s hole. At first sight, the whole system used a normal AES encryption, but we found some interesting mechanics dealing with the key derivation logic.

Disclaimer

This article is going to lack many details that may be used to identify the DRM system in question. Our focus will be on the reverse engineering process and the tools used to reach the final goal.

We don’t want to disrupt the business of the companies using this specific DRM, our aim was pointing out how, once again, DRM prove useless against a motivated attacker.

What is a DRM

Digital Rights Management are often used to secure digitally distributed media content. A well known example is Widevine by Google, used by Netflix, Amazon Prime Video, HBO, Disney+…

The basic concept of a DRM lies in hiding the actual content behind an encryption or scrambling layer to avoid basic copy-paste redistribution. The only non encrypted parts are user-dependent information needed by the DRM ecosystem to manage and control the digital media itself, in our case: redeem time, media availability and signing data to prevent tampering.

Android app

We started the reverse engineering process decompiling the Android app in order to figure out the data flow.

Some basic text search in the codebase, looking for the text used in the password prompt, led us to the part of the code where the password was manipulated by the app. The user input was hashed with SHA256 and stored in a password database for later use. When the app needed plaintext data, it passed the password database along protected content to a native function which returned the decrypted content. We assumed the lib might have been using standard crypto and tried to guess the encryption algorithm via some more text search. Strings in the app pointed out AES256 as a possible candidate, a guess validated by the key size, which matches the output of SHA256. With this basic information, we naively tried to decrypt the content we had with the hash of our passphrase, to no avail.

Native lib

Given our initial attempt was unsuccessful, we had to take a deeper look at the native library, which at this point was probably doing something more than mere decryption. We imported the binary into Ghidra and started to reverse it the old fashioned way.

Java (and Android runtime specifically) allows executing native code using JNI, the Java Native Interface. Due to how the JNI works internally, the bridging functions can be easily identified in the binary given the method called in Java. This eased our analysis of the library since we knew where to start reading the binary and also knew the parameters being passed to native code.

This excellent article from Maddie Stone’s blog explains how to actually reverse engineer JNI native code and gives some really useful advices to make the code more readable in the decompiler. For example, loading this gist from jcalabres and defining the first parameter as a JNIEnv_ struct type allows Ghidra to show JNI bridge methods such as CallObjectMethod, GetStaticIntField and alike.

Using Frida, we attached the Java function invoking the JNI to retrieve the actual parameters.

// Anonymized code

Java.perform(function() {

var DRM_class = Java.use('org.vendor.drm.sdk');

// We have to attach the DRM class constructor because

// at this point we're sure the .so object is in the classpath

DRM_class.$init.implementation = function() {

this.$init(); // Call actual Java constructor

// Add our own hook

Interceptor.attach(Module.findExportByName('libdrm.so', 'Java_org_vendor_drm_sdk_nativeCheckPassword'), {

onEnter: function(args) {

console.log("Attached CheckPassword");

console.log("jsonData:", readJString(args[2]));

},

onLeave: function(args) {

console.log("Leaving CheckPassword");

}

});

}

});

/* Read a JString (Object passed via the JNI) from C++ code */

function readJString(str_ptr) {

var ret_str;

Java.perform( function () {

var String = Java.use("java.lang.String");

ret_str = Java.cast(ptr(str_ptr), String);

});

return ret_str;

}

Once we knew the parameters being passed, we fixed the stack and redefined data types in Ghidra to make the pseudocode more accurate and readable. Then we started to actually reverse engineer the native function accepting this data. It proved to be basically a simple loop on all the keys in the passphrase database, which was passed by the Android application, checking them one by one decrypting a known plaintext. We could easily identify the crypto algorithm, since a well known C++ crypto library was in use and the crypto parameter clearly stated AES-256/CBC.

Luckily Frida supports native function hooks as well, although the hooking process is fairly more convoluted than with Java. For example, C++ strings are complex objects that require more than a simple “memory read” to be printed.

/* Read a C++ std string (basic_string) to a nomal string */

function readStdString(ptr_str) {

const isTiny = (ptr_str.readU8() & 1) === 0;

if (isTiny) {

return ptr_str.add(1).readUtf8String();

}

return ptr_str.add(2 * Process.pointerSize).readPointer().readUtf8String();

}

/* Read a C++ std vector

* Copied and slightly modified from https://github.com/thestr4ng3r/frida-cpp

*/

class StdVector {

constructor(addr, options) {

this.addr = addr;

this.elementSize = options?.elementSize ? options.elementSize : Process.pointerSize;

this.introspectElement = options?.introspectElement;

}

get myfirst() {

return this.addr.readPointer();

}

get mylast() {

return this.addr.add(Process.pointerSize).readPointer();

}

get myend() {

return this.addr.add(2 * Process.pointerSize).readPointer();

}

countBetween(begin, end) {

if(begin.isNull()) {

return 0;

}

const delta = end.sub(begin);

return delta.toInt32() / this.elementSize;

}

get size() {

return this.countBetween(this.myfirst, this.mylast);

}

get capacity() {

return this.countBetween(this.myfirst, this.myend);

}

toString() {

let r = "std::vector(" + this.myfirst + ", " + this.mylast + ", " + this.myend + ")";

r += "{ size: " + this.size + ", capacity: " + this.capacity;

if(this.introspectElement) {

r += ", content: [";

const first = this.myfirst

if(!first.isNull()) {

const last = this.mylast;

for(let p = first; p.compare(last) < 0; p = p.add(this.elementSize)) {

if(p.compare(first) > 0) {

r += ", ";

}

r += this.introspectElement(p);

}

}

r += "]";

}

r += " }";

return r;

}

}

Once we figured out how to read the parameters, we quickly noticed that the passphrase being used actually to decrypt the data was different from the one provided by Java call. It became clear that some kind of key derivation was being in used.

Still using Frida, we analyzed the input and output of every function separating the JNI call to the decryption routine: to our surprise a function called something along the lines of boring_function_doing_nothing_relevant was responsible for the actual key derivation. This made us waste way more time than we’d like to admit, but we now know better than ever to NEVER trust symbols and developers.

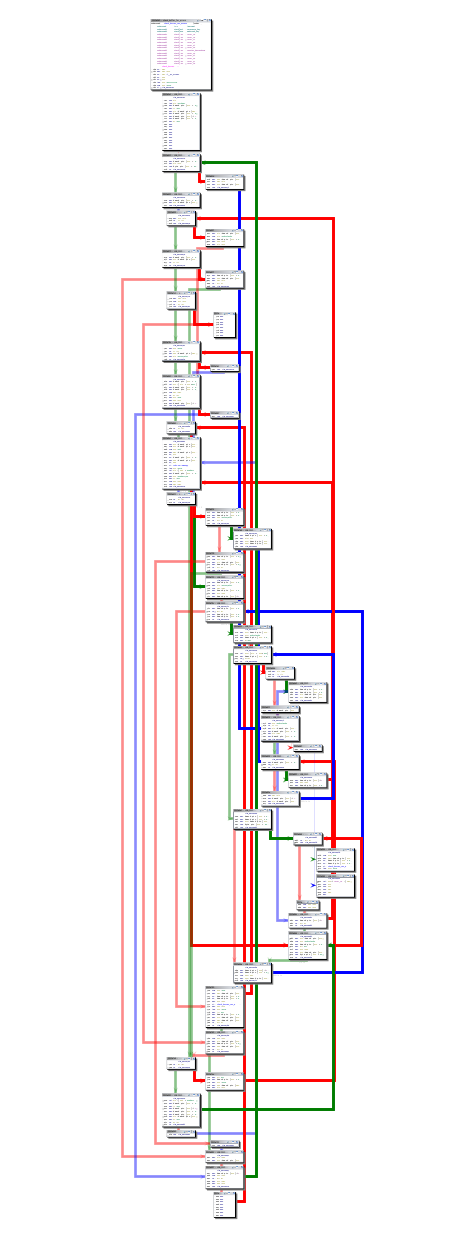

The boring_function_doing_nothing_relevant function turned out to be implemented as a complex state machine, way too annoying to statically reverse with Ghidra.

boring_function_doing_nothing_relevant function graph

Fearing we might have to deal with white-box crypto (which is almost impossible to reverse), we decided to use Unicorn, a powerful framework build upon QEMU, to emulate this portion of code. Once we got the binary to run, and it outputted correct data, our plan was to analyze code flow and stub different parts of the function one at a time. That would allow us to understand the behavior of narrow parts of the code, and then figure out the whole algorithm.

Following the examples in Unicorn’s GitHub repo, we loaded the binary in memory and allocated space for stack and additional data. On the other hand, patching/reimplementing library function calls (such as memcpy) and adjusting Unicorn virtual registers accordingly was a little more challenging.

Eventually, we managed to run correctly every function we needed, but, to our great surprise, the derived key was not matching the one coming from execution in actual hardware.

Dazed and confused we checked our instrumentation code to spot any emulation mistake and found none (to our knowledge), double-checked the stack and external function re-implementation. We then started to trace the function call, in emulation and real hardware execution with GDB, to evaluate possible differences in code flow. No dice, but we started to get a grasp on how the algorithm worked. We finally ended up comparing data on a per-register level upon every executed instruction, instrumenting GDB with this code

import binascii

import struct

import gdb

class RegDumper(gdb.Command):

"""Dumps registers in a parsable manner"""

def __init__(self):

super(RegDumper, self).__init__("regdump", gdb.COMMAND_USER)

self.pagination = gdb.parameter("pagination")

def invoke(self, args, from_tty):

ret_list = []

# Get function's last instruction address (considering ASLR offset). +1100 comes from disasm code

function_ret = gdb.execute('x/1i boring_function_doing_nothing_relevant+1100', to_string=True).strip().split(' ')[0]

this_dic = {}

while this_dic.get('eip', 0) != function_ret:

# Stop stepping as soon as we're leaving the target function

registers = ['eax', 'ebx', 'ecx', 'edx', 'esp', 'ebp', 'esi', 'edi', 'eip']

this_dic = {}

if self.pagination: gdb.execute("set pagination off")

for reg in registers:

reg_str = str(gdb.selected_frame().read_register(reg)).split(' ')[0]

if '0x' in reg_str:

this_dic[reg] = reg_str

else:

this_dic[reg] = '0x'+str(binascii.hexlify(struct.pack('>i', int(reg_str))).decode('ascii'))

ret_list.append(this_dic)

gdb.execute('nexti', to_string=True) # Don't print to term

print(ret_list)

if self.pagination: gdb.execute("set pagination on")

RegDumper()

Then, we finally noticed how the sha256-related functions, built into the library itself, were returning an incorrect hash only while being emulated in unicorn. We didn’t even bother to figure out WHY that was yielding wrong data (we were really done with it), and we just patched it away, replacing it with pycrypto’s SHA256 implementation and shoving the final result directly in memory.

import hashlib

import struct

import hexdump

from unicorn import *

from unicorn.x86_const import * # for accessing the registers

X86_CALL_SIZE = 5 # CALL instruction size in bytes

hash_ctx = None

### REDACTED CODE ###

def sha256_init(uc, address, size, user_data):

print("sha256 INIT")

global hash_ctx

hash_ctx = hashlib.sha256()

uc.reg_write(UC_X86_REG_EIP, uc.reg_read(UC_X86_REG_EIP) + X86_CALL_SIZE) # Move IP to next instr

def sha256_update(uc, address, size, user_data):

global hash_ctx

data_ptr_barray = uc.mem_read((uc.reg_read(UC_X86_REG_ESP) + 0x4), 0x04)

data_size_barray = uc.mem_read((uc.reg_read(UC_X86_REG_ESP) + 0x8), 0x04)

data_ptr = struct.unpack('<I', data_ptr_barray)[0]

data_size = struct.unpack('<I', data_size_barray)[0]

data = uc.mem_read(data_ptr, data_size)

print(f"sha256 UPDATE - src: {data_ptr:x} - size: {data_size:x}")

hexdump.hexdump(data)

hash_ctx.update(data)

uc.reg_write(UC_X86_REG_EIP, uc.reg_read(UC_X86_REG_EIP) + X86_CALL_SIZE) # Move IP to next instr

def sha256_final(uc, address, size, user_data):

global hash_ctx

dst_ptr_barray = uc.mem_read((uc.reg_read(UC_X86_REG_ESP) + 0x4), 0x04)

data_ptr = struct.unpack('<I', dst_ptr_barray)[0]

digest = hash_ctx.digest()

uc.mem_write(data_ptr, digest) # Write actual hash in memory where it is supposed to be

print(f"sha256 FINAL - dest: {data_ptr:x}")

hexdump.hexdump(digest)

hash_ctx = None # Reset global hashing context

uc.reg_write(UC_X86_REG_EIP, uc.reg_read(UC_X86_REG_EIP) + X86_CALL_SIZE) # Move IP to next instr

### REDACTED CODE ###

uc = Uc(UC_ARCH_X86, UC_MODE_32)

uc.hook_add(UC_HOOK_CODE, sha256_init, begin=0xDEADBEEF, end=0xDEADBEEF) # SHA256_Init

uc.hook_add(UC_HOOK_CODE, sha256_update, begin=0xBEEFBABE, end=0xBEEFBABE) # SHA256_Update

uc.hook_add(UC_HOOK_CODE, sha256_final, begin=0xDABBAD00, end=0xDABBAD00) # SHA256_Final

Finally, we got the correct result.

Figuring out the algorithm

By this time, due to the tedious debugging process we had to go through, we understood how the key derivation worked at a surface level; it can be summed up by the following snippet:

data = input_key

for i in range(0,64):

data += calc_one_byte_somehow()

data = SHA256(data)

We then were still missing out the behavior of the aptly named calc_one_byte_somehow function. To figure out this last bit, we started to feed into our emulation “easy” values such as 32 bytes of zeros or 32 bytes of ones. To our surprise, the result of calc_one_byte_somehow was unchanged. After a couple of extra tests, we concluded that the appended bytes, albeit calculated at runtime, were always the same and completely unlinked from supplied data.

Finally, the whole DRM’s key derivation system was replaced by a 10 lines python script, once we dumped the “secret bytes” via our stubbed SHA functions. We didn’t even bother to understand the bytes generation algorithm.