Weaponizing a NFC reader for basic timing attacks

Oct 24, 21

I am currently (since a couple of years, actually) in the process of reverse engineering an undocumented “secure” NFC tag with friends. It is widely used, but, to the best of my knowledge, nobody else is actively working on it.

By the way, secure is put into quotation marks as the company’s security model is based upon NDA’d documentation and a custom mutual authentication algorithm.

Basics

Since we are standing on the shoulders of giants, I tried to follow the steps taken by other researches such as Nohl, Plötz and Starbug’s. They noticed a serious weakness in the PRNG of Mifare tags, which was exploited by other researchers (de Koning Gans, Hoepman, Garcia) leading to the cryptography being broken. To do so they first had to implement ISO14443-A codec in the Proxmark’s FPGA, in order to have precise timings.

This product is reported to use a “true random number generator” on the vendor website, but I wondered if that was actually true.

First attempt

The tag I’m dealing with is not compliant to ISO14443-A, but to ISO15693 (iso15 from now on) which is, of course, not implemented in FPGA on the Proxmark. Support for this standard instead relies heavily on the ARM MCU and therefore does not provide precise timings. I did not want to go through the effort of touching once again Proxmark’s codebase without knowing whether this approach could have lead to any useful data. So I resorted to use the CR95HF demo board, one of the cheapest NFC dev kits available on the market. I modified an older script and used the board to:

- Turn off the field

- Turn back on the field

- Issue a “Get random nonce” command

These 3 commands, in a tight while loop, were sent as HID packets via USB to the demo board. I turned the field off and then back on in order to minimize the entropy fed into the PRNG to, hopefully, maximize hit rate of repeated nonces.

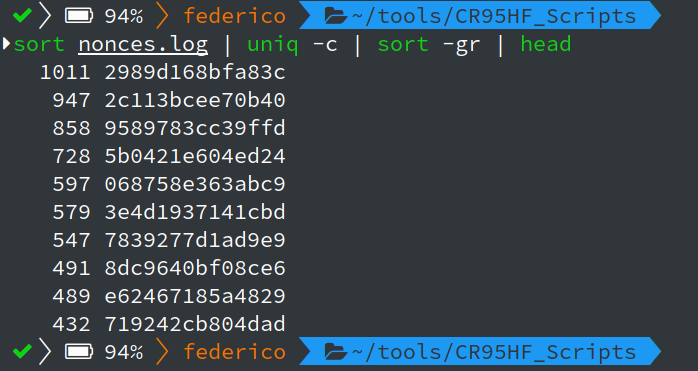

This solution, albeit extremely naive, led to very interesting results:

After 460.000 attempts (line count not shown), which were harvested in something less than 50 minutes, there were already more than 1000 repetitions of the same nonce. A couple of other nonces had a slightly lower occurrence rate, but still way higher than the average, thus something’s off with the PRNG.

Now, while this approach was already yielding promising results, it would be nice to improve it. 1/500 hit rate is not bad, but it isn’t that good either. Also, there were issues with the reliability: sometimes there were no repetitions at all.

As you can see from the below oscilloscope capture, the beginning of modulation is quite “wobbly”, drifting in time in a 10 μs windows. This was probably due to the fact the board was directly driven from my laptop via USB HID and so many things could go wrong there.

Hacking a NFC reader’s firmware

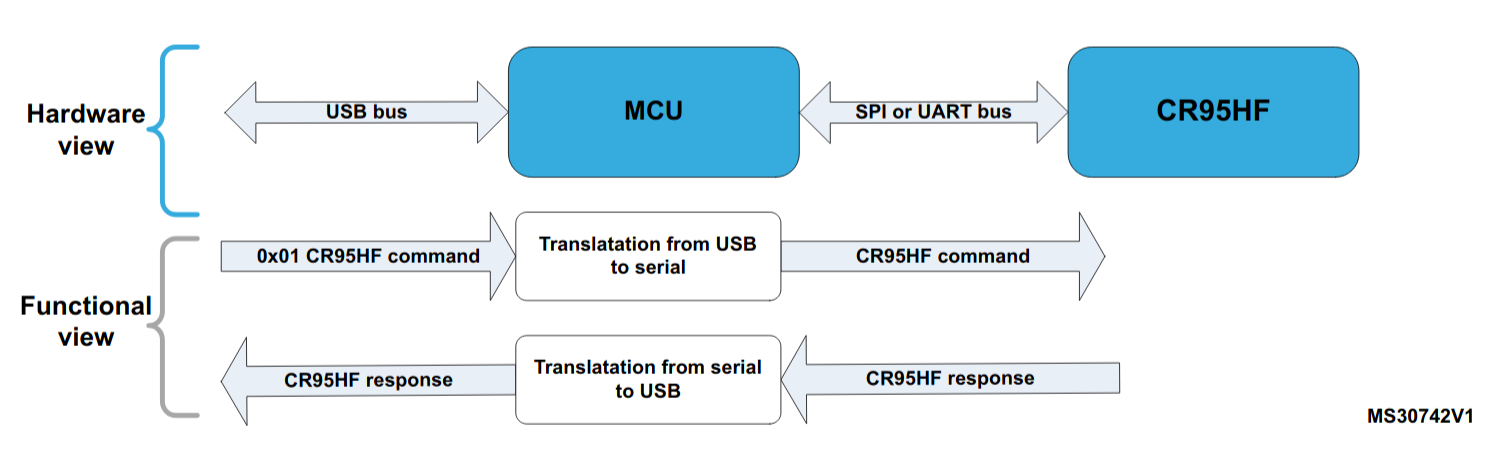

Other than being cheap, the CR95HF demo board has the great advantage of being fully open source.

Here is a diagram from the firmware documentation to explain how communication between the computer and the CR95HF front end works.

The firmware running on the STM32F103 is, of course, downloadable as well, and it can be built with ARM-MDK importing the DEMO_BOARD_CR95HF.uvprojx file in the project archive.

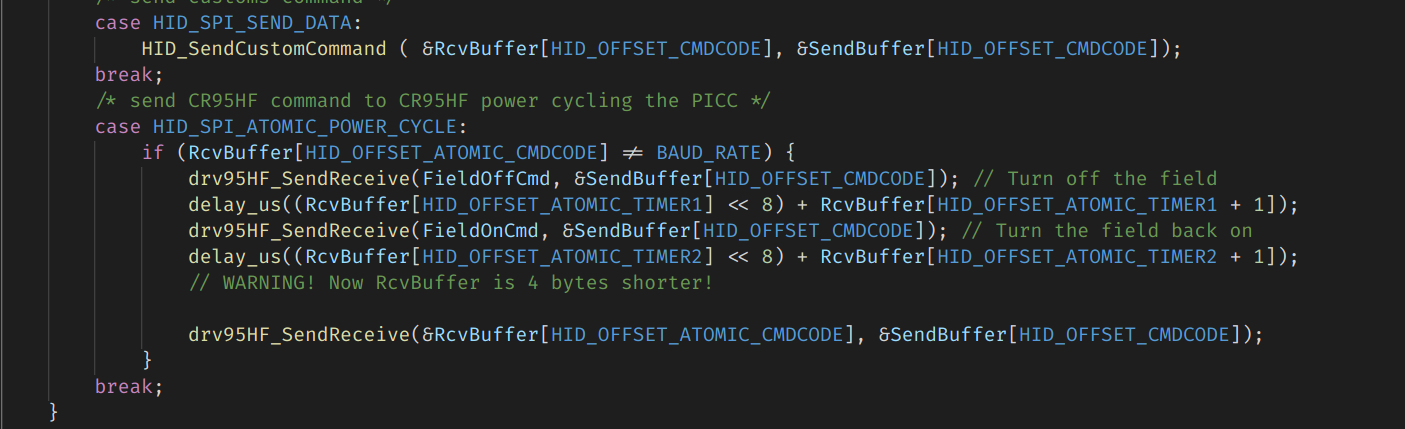

At this point a friend joined me, and we started to hack the firmware. We implemented a very basic jitter buffer in the firmware, adding our own custom HID_SPI_ATOMIC_POWER_CYCLE command to integrate HID_SPI_SEND_CR95HFCMD, the one I was using in my script earlier. The new command should be fed 4 parameters:

- Time1: Amount of time (in μs) to wait after turning off the field before turning it back on

- Time2: Amount of time (in μs) to wait after turning on the field beforr starting to modulate the command to the tag

- Length of data

- Data: The command itself

This way all the waits could be performed on the STM32 MCU, without any overlapping task which could take precedence over our packets and, hopefully, delivering repeatable results. We also had the possibility to edit all the parameters on the computer side, without the need to recompile the firmware every time we wanted to try new timings or add normal commands in between.

After some wrestling with the libraries provided by ST (the FieldOn function does not behave as expected and the wait_us interrupt Autoreload, AKA interrupt period, is halved) we got a working build. It could be easily flashed on the board with an ST-Link via uVision (the MDK version!) itself.

So, how accurate was the result?

Sub-1 μs precision can be considered bang on, as far as I’m concerned. The modified firmware can be found on GitHub.

Timing attacks!

Once the firmware had been patched, the easy part was over. Now it came the time to figure out what was going on inside the silicon.+

We started to peek around with different timings, trying to replicate the results, but we never succeeded. Given the really unsatisfactory results, we even tried the old unreliable HID script again, to no avail. Multiple days of unsuccessful tests later, we figured out that the positioning of the tag on the reader was critical: a 2° rotation of the card around the center of the reader antenna could mean the difference between zero and thousands of repetitions. For this reason, the setup process is extremely tedious, but luckily, when they happen, collisions are quick, so few (couple of thousands) nonce requests are enough to see the first repetitions. We had best luck with the card center aligned on the CR95HF’s antenna center and a ~20° clockwise rotation, YMMV.

This behavior tells us that most likely the tag contains a TRNG, which is fed with some kind of entropy from the NFC field. This is indeed an intelligent solution, since in a real world scenario the tag is being moved by the user within the field in a non-deterministic manner, thus yielding actually random values.

On the other hand, when the tag is power cycled in a controlled environment, collisions happen, so the TRNG probably does not retain state.

Trying to figure out if the random generation had a specific period (as it happened with Mifare tags), we tried to identify a possible counter overflow. Waiting for too much time to request a nonce after the field power-up resulted in no collisions, so probably the TRNG diverges from a clean state as time passes. Using a fixed short time didn’t yield wonderful results either, so we tried to “sweep” waits in order to intercept the best timing.

The holes in the field are the modulated bits in reader->tag communication

The holes in the field are the modulated bits in reader->tag communication

As soon as a repeated nonce is found, the current wait time is used as a reference and other nonces are requested in the surrounding of the same interval. This approach led to some improvements, but it was mostly inconclusive, to be honest.

Also, it’s worth noting that every time a tag was removed and reseated on the reader, the collisions happened with different nonces. If on one run the most common nonce was 32f0c2a660da4c, on the following it might be 45e5d88e833c28. This could be very well related to the inaccuracy of our test setup (we didn’t have a repeatable positioning jig), but it’s worth noting since it shows how the TRNG is heavily influenced by the field and/or other still unknown factors.

Conclusions

My first test was exceptionally lucky: if no repetitions occurred I wouldn’t have spent more times diving into this issue, thanks to that lucky draw, we now know that this tag is flawed.

We didn’t perform further testing since this project was started early 2020, then COVID hit, and we were stuck at home. I’d like to work on this thing again sooner or later, but I’m unsure if conclusive results could be gathered from black box analysis only. Most likely the only way to know what’s going on would be analyzing the silicon.

By the way, our firmware is backwards compatible with the demo software provided by ST or with scripts you can find online.